Former Red Deerian shares recovery journey from drugs and crime, suggests possible solutions

It was his third time in the Bowden federal penitentiary. On the inside, Anton Kokol wasn’t even worth a four-dollar daily job anymore; he was an ever-returning old-timer. But volunteering to mop the floors for free was better than 22 hours a day in his cell. He finished cleaning and sat down on the couch. Looking up, he saw a group of senior inmates pacing back and forth. At 46 years old, it hit him.

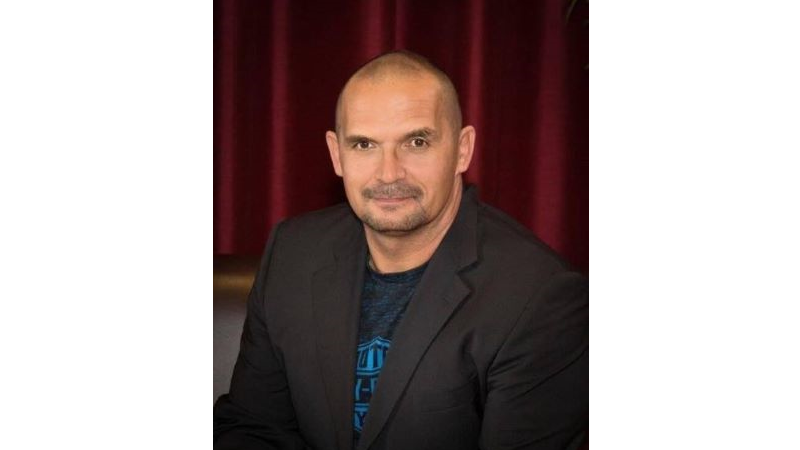

“I was like, ‘I am not doing my 50s in here. I am not doing my 60s,” said the now 61-year-old Recovery Companion and Coach. “Something changed that day on that bench.”

The former Red Deerian will also be sharing his journey out of drugs and crime at the Alberta Community Crime Prevention Association annual conference this May 6-8.